Music Generation with Deep Neural Networks, Bach and Beyond

By Karl Konz

Prior to becoming a data scientist, I was lucky enough to study in one of the finest graduate orchestral percussion programs in the world. Most of my classmates during that time now have big orchestra jobs such as the Metropolitan opera and the Oregon Symphony. The program was very structured and formulaic and I am convinced that having studied under Tom Freer laid the foundation for me to have the capacity to do well in data science. So, thank you Tom! Whenever I get a chance, I love to work on a music data modeling project. This is the most ambition project I have tried yet and has also turned out to be the most rewarding.

For this post I will explore the limits of the deepBach modeling approach to generate music with deep neural networks.

The code is open sourced and can be found under SONY deepBach, the Bach chorale corpus for that research is readily available in the music21 package. I wanted to explore expanding the corpus to include compositions from after the baroque period as well. One of the constraints of this modeling technique is that there must be the same number of voices for each training composition. The Bach files used for the initial research have four part harmonies so I decided to add string quartets from the classical, romantic, and nationalist periods as they have the same number of voices.

Additional data, string quartets

In addition to the roughly 350 Bach chorale files from the original research, I am added 189 string quartet midi files from Beethoven, Mozart, Shostakovich, Brahms, Schumann, Schubert, and others. To gather the additional string quartet midi files, I wrote a script to scrape the files I wanted from site Kunst Der Fuge with Selenium using the Python wrapper. Below is a snippet for this was achieved, I used the gecko driver with Firefox to obtain the additional string quartets.

If you have pip installed on your computer, you can use the following command to download the python library.

pip install -U selenium

Follow the Gecko driver instructions to download the appropriate driver for Firefox.

Next setup the preferences for the browser.

# Instantiate a webdriver profile

firefox_profile = webdriver.FirefoxProfile()

# Disable the prompt asking to whether and where to save the file

firefox_profile.set_preference("browser.helperApps.neverAsk.saveToDisk", "audio/midi")a

firefox_profile.set_preference("browser.download.folderList", 2)

firefox_profile.set_preference("browser.download.dir", "<Path to download file into>")

firefox_profile.set_preference("browser.download.manager.showWhenStarting",False)

# Launch the browser with the appropriate settings

driver = webdriver.Firefox(firefox_profile=firefox_profile)

# Get the Kunst Der Fuge URL

driver.get('http://www.kunstderfuge.com/-/db/log-in.asp')

Before continuing, make sure that you have subscribed to Kunst Der Fuge website if you haven’t already. I am frugal so I chose to pay less and scrape the files I wanted. If you want to skip this process and pay more you can download the midi database.

Next Authenticate into the website in order to access the files.

# Create a username object with your username

username = driver.find_element_by_id("Email")

# Send the Username to the approprate element with the 'Email' id

username.send_keys("<username>")

# Create a password object with your password

password = driver.find_element_by_id("Password")

# Send the password to the appropriate element with the 'password id

password.send_keys("<password>") # Enter password

# Click the submit button

driver.find_element_by_name("Submit").click()

After authenticating into the website, we will need to navigate to the midi section of the website.

# find all the midi elements by xpath

MIDI = driver.find_elements_by_xpath("//*[text()='MIDI']")

# Extract the midi elements

for ii in MIDI:

link = ii.get_attribute('href')

# navigate to the link midi attribute

driver.get(link)

The last step is to download the actual string quartets, below is the method used to extract the Beethoven files. The full script can be found here, note that the format of the website varies a bit from composer to composer.

# find the Beethoven Chamber element by xpath

BeethovenChamber = driver.find_elements_by_xpath("//*[text()='Chamber music']")

# extract the URL for the the xpath

for ii in BeethovenChamber:

link = ii.get_attribute('href')

# Navigate to the Beethoven Chamber music page

driver.get(link)

# Click on each of the quartet midi links

elems = driver.find_elements_by_xpath("//a[contains(@href, 'quartet')]")

for elem in elems:

elem.click()

time.sleep(3)

By adding the string quartet files there was a 730% increase in the count of notes from what was used in the original deepBach study. So there was just over half the number of string quartet files as Bach files, however the string quartet files contain much more notes. I experimented with subsetting the string quartets into smaller files to sort of standardize the size of the files, but that approach did not yield very compelling or statistically accurate results.

I also conducted a z test to check the proportion of the notes in terms of frequency and note duration combinations as plotted below, the p value from the test was 7x10-43, thus there is evidence of a difference in the proportion of notes between the Bach chorales and the new string quartets I added. Below is the code I used to conduct that test.

I used the music21 package to analyze the note compositions of the Bach data set and the String Quartets separately. If pip is installed, the following snippet can be used to download the package.

pip install music21

We can see that notes with smaller durations are more common in the string quartet files than in the Bach Chorale files. In other words, it is more common to have faster notes in the string quartets than in the Bach compositions. See my Project Build for more details on this project.

Initially the string quartet files were chopped into 20 measure sequences, this proved to be problematic. Complex subdivisions would have infinite durations when converting to ‘streams’ from the music21. What ultimately worked the best was training on the full midi files as opposed to slicing the midi files into smaller sequences.

Training the model

The first step in training this model is to transform the data into different one-hot encodings. This is the process of transforming the data into binary vectors where each categorical value is mapped to integer values. Each vector will be all zeros except the index with the given value which is represented as a 1. The code block below is borrowed from the tensorflow website.

indices = [0, 1, 2]

depth = 3

tf.one_hot(indices, depth) # output: [3 x 3]

# [[1., 0., 0.],

# [0., 1., 0.],

# [0., 0., 1.]]

indices = [0, 2, -1, 1]

depth = 3

tf.one_hot(indices, depth,

on_value=5.0, off_value=0.0,

axis=-1) # output: [4 x 3]

# [[5.0, 0.0, 0.0], # one_hot(0)

# [0.0, 0.0, 5.0], # one_hot(2)

# [0.0, 0.0, 0.0], # one_hot(-1)

# [0.0, 5.0, 0.0]] # one_hot(1)

indices = [[0, 2], [1, -1]]

depth = 3

tf.one_hot(indices, depth,

on_value=1.0, off_value=0.0,

axis=-1) # output: [2 x 2 x 3]

# [[[1.0, 0.0, 0.0], # one_hot(0)

# [0.0, 0.0, 1.0]], # one_hot(2)

# [[0.0, 1.0, 0.0], # one_hot(1)

# [0.0, 0.0, 0.0]]] # one_hot(-1)

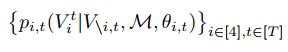

This model follows metadata sequences in which the conditional probability distribution is defined below:

Vit indicates the voice i at time index t and

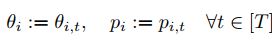

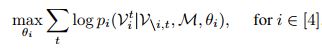

Then each of the conditional probability distributions are fit to the data by maximizing the log-likelihood. This results in four classification problems represented mathematically below:

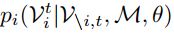

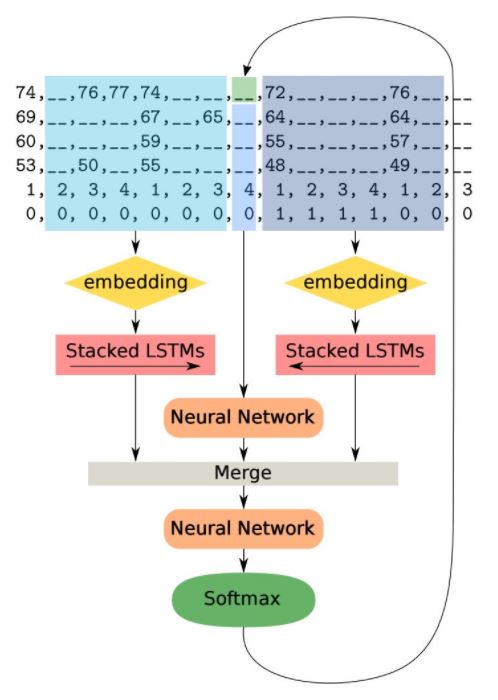

This in effect predicts a note, based off the value of its neighboring notes. Each classifier is fit using four neural networks. Two of which are deep neural networks, one dedicated to summing past information and the other summing future information in conjunction with a non-recurrent NN for notes occurring at the same time. The output from the last recurrent neural network is preserved and the three outputs are merged and used in the fourth neural network with output:

The illustration below shows the stacked models described above:

Generation in the dependency networks is done by utilizing pseudo-Gibbs sampling, where the conditional distributions are potentially incompatible and that the conditional distributions are not necessarily from a joint distribution p(V). This Markov chain does converge to another stationary distribution and applications on real data demonstrated this method yielded accurate joint probabilities.

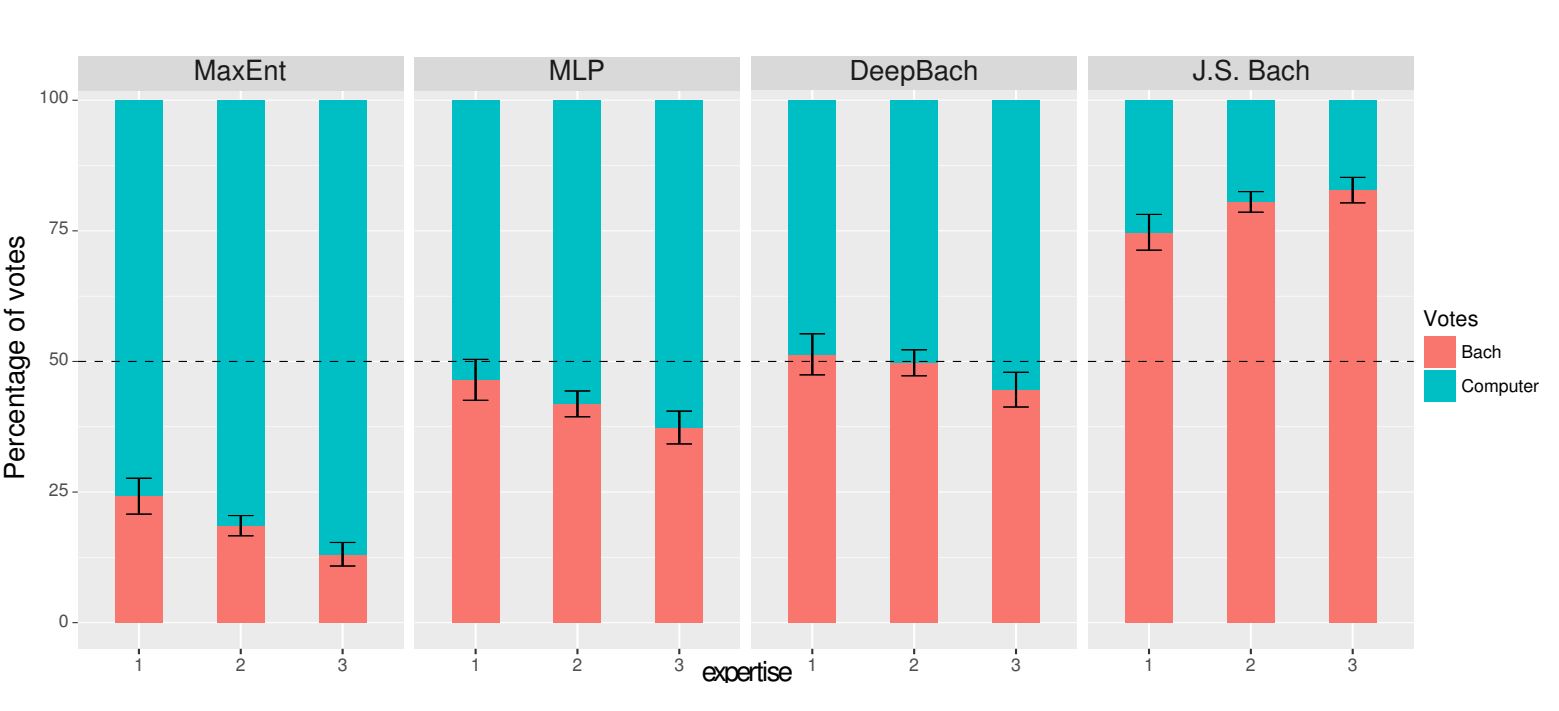

The results from this modeling technique seem to speak for themselves. See the results of the “Bach or Computer” experiment below. The figure shows the distribution of the votes between “Computer” (bluebars) and “Bach” (red bars) for each model and each level of expertise of the voters (from 1 to 3). The J.S.Bach field are actual Bach compositions and MLP stands for a multi-layer perceptron and MaxEnt stands for Maximum Entropy.

I had issues running the source code on my windows machine and ended up having to just hard code the pickled data set path and name instead of using the os python package. The code I used to actually train the AI music embedded below is available KKONZ deepBach. I ran the code on an Azure Deep Learning VM with NVIDIA GPUs to shorten the training time. Note that this version does not use Keras 2 yet. After cloning the github repository you will also need to download a couple libraries music21 and tqdm:

git clone "http://github.com/kkonz/DeepBach"

pip install music21

pip install tqdm

Then using the following parameters, you can adjust the following parameters and start modeling right out of the box. To adjust optimizer settings you will need to do so in the deepBach.py file.

usage: deepBach.py [-h] [--timesteps TIMESTEPS] [-b BATCH_SIZE_TRAIN]

[-s SAMPLES_PER_EPOCH] [--num_val_samples NUM_VAL_SAMPLES]

[-u NUM_UNITS_LSTM [NUM_UNITS_LSTM ...]] [-d NUM_DENSE]

[-n {deepbach,skip}] [-i NUM_ITERATIONS] [-t [TRAIN]]

[-p [PARALLEL]] [--overwrite] [-m [MIDI_FILE]] [-l LENGTH]

[--ext EXT] [-o [OUTPUT_FILE]] [--dataset [DATASET]]

[-r [REHARMONIZATION]]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--timesteps TIMESTEPS

models range (default: 16)

-b BATCH_SIZE_TRAIN, --batch_size_train BATCH_SIZE_TRAIN

batch size used during training phase (default: 128)

-s SAMPLES_PER_EPOCH, --samples_per_epoch SAMPLES_PER_EPOCH

number of samples per epoch (default: 89600)

--num_val_samples NUM_VAL_SAMPLES

number of validation samples (default: 1280)

-u NUM_UNITS_LSTM [NUM_UNITS_LSTM ...], --num_units_lstm NUM_UNITS_LSTM [NUM_UNITS_LSTM ...]

number of lstm units (default: [200, 200])

-d NUM_DENSE, --num_dense NUM_DENSE

size of non recurrent hidden layers (default: 200)

-n {deepbach,skip}, --name {deepbach,skip}

model name (default: deepbach)

-i NUM_ITERATIONS, --num_iterations NUM_ITERATIONS

number of gibbs iterations (default: 20000)

-t [TRAIN], --train [TRAIN]

train models for N epochs (default: 15)

-p [PARALLEL], --parallel [PARALLEL]

number of parallel updates (default: 16)

--overwrite overwrite previously computed models

-m [MIDI_FILE], --midi_file [MIDI_FILE]

relative path to midi file

-l LENGTH, --length LENGTH

length of unconstrained generation

--ext EXT extension of model name

-o [OUTPUT_FILE], --output_file [OUTPUT_FILE]

path to output file

--dataset [DATASET] path to dataset folder

-r [REHARMONIZATION], --reharmonization [REHARMONIZATION]

reharmonization of a melody from the corpus identified

by its id

I then added a midi file of the Led Zeppelin track Kashmir and reharmonized the model to that track and going to California as well, both were trained in the same manner as the code above, but were deliberately named in a way to be indexed in the first position. Here are sample outputs from those models:

Results:

Kashmir:

Going to California:

Deep Going To California by Konzert

Conclusions:

When choosing a file to reharmonize, it seemed that files where all of the voices are moving train more compelling output than when the voices more or less just outline the harmonic changes in block chords. Overall, I was happy with the output from this modeling technique and this has been an incredibly rewarding project to work on. The vast majority of the classical music that I have studied is orchestral music, listening to and modeling the string quartets has given me extra appreciation for the composers that I have long enjoyed. While, in my opinion, the music of Beethoven and Mozart is irreplaceable this approach allows us to merge the styles of various composers and get a fresh perspective on their collective genius.